"Infamy and Infidelity"

the Barry and Somerset sodomy scandal, freedom of the press, 1820s sex between men and colonial sex scandals

Warning: this article discusses period typical state and social violence against men who had sex with other men including public executions. This article also contains reference to suicide, sexual assault and public outing.

In Cape Town on June 1st, 1824 a placard was attached a bridge at the crossroads of several main Cape Town streets declaring that Lord Charles Somerset had been seen buggering Dr. James Barry.

Even though the placard was quickly torn town the accusation spread through Cape Town and within the day it had become a full-blown scandal. By the end of the week an official government investigation into the origins of the placard was under way.

The case has largely not been studied within the wider context of sodomy scandals. This is probably because Barry's involvement has kept writers from viewing the Barry/Somerset scandal as a 'real sodomy' scandal. Regardless of Barry's assigned gender though, the sodomy scandal he and Somerset found themselves embroiled in on June 1st was very much a real sodomy scandal.

Both Barry and Somerset presented themselves as men and would do so for the rest of their lives. They were both viewed exclusively as men professionally, socially, and privately. As far as both the public and private letters and documents we have from both Somerset and Barry are concerned they both viewed each other as men as well. They were also well known for having a close, loving relationship with each other that pushed beyond the socially acceptable limits of friendship.

So when the accusation of sodomy was made not only did it come with very real consequences for both Barry and Somerset but it also fit into much larger narratives of sodomy accusations during the early 19th century, the role of the press in these scandals, and the use of sex scandal in policing colonial British society.

June 1824 was the worst time for the scandal to happen for both Barry and Somerset. Barry was embroiled in the C. F. Liesching licensing episode while Somerset's political support back in England had been steadily waning. Both were on some of the thinnest political ice they'd been since arriving in Cape Town. The very last thing either of them needed that summer was to be involved in a scandal, particularly one of this magnitude and severity.

In 1824 being found guilty of sodomy, forced sodomy or attempted sodomy under British law could lead to prison, transportation, pillorying or death.

(A pamphlet reporting on the execution of D. T. Myers for sodomy in 1812, courtesy of the British Library)

Lord Charles Somerset was the son of a duke and, more importantly, the highest authority in the Cape Colony. The likelihood that he would be imprisoned or punished was low. According to testimony during the investigation that followed over the next month though, when Barry first heard details of the accusation and how far through Cape Town society it had spread he broke down in tears. It was an unusual reaction him since he usually responded to threats with anger and frantic action.

Almost immediately the investigation into exactly who was behind the placard began. Denyssen, His Majesty's Fiscal, took the lead on the investigation. Despite him and Somerset's personal animosity, the accusations were an attempted strike at the stability of the British government in the Cape Colony and it was in everyone's favor to show a united front and shut down the entire scandal as quickly as possible before it could spiral out of control.

Over the next month, Denyssen brought forward two suspects he believed were responsible for posting the placard, Mr. George Greig and Mr. William Edwards.

They were identified as being responsible in an anonymous letter sent to Barry shortly after the scandal broke, which he had passed on to Denyssen, and in the testimonies given by several servants.

George Greig's was a printer who, along with Thomas Pringle and John Fairbairn, produced the South African Commercial Advertiser. William Edwards was an ex-solicitor and a well-known figure to everyone involved in the scandal. Only a month or so earlier he had been tried and found guilty for libel against a laundry list of government officials including Somerset and Barry. Most of the accusations that during contested during the trial had to do with government corruption. Edwards had accused key government officials of mismanaging the colonies assets as well as cronyism. Many of these accusations he continued to stand by even in court. Where Barry was concerned Edward's argued that it was unfair for one individual to hold as many civil service positions as Barry did, meaning that he was paid three different salaries, although none of them very large. Edwards had also pointed out that there seemed to be one law for most of the other doctors and pharmacists in the Cape Colony and then a completely different set of laws for the doctors and pharmacists in Somerset's good graces, particularly Barry.

For Barry, who was already involved in the pharmacist licensing issue with Liesching, this point, in particular, must have been a touchy subject. Edwards also added insult to injury by referring to Barry publicly as "Little Barry." Barry, who was particularly sensitive about his height took great offense. Along with political attacks and the jab at Barry's expense Edwards had also made public comments about Somerset's eldest daughter, which Somerset took great offense to.

All this was enough to see Edwards tried and convicted. He was stripped of his ability to practice law in the Cape Colony and sentenced to transportation. His reasons for posting the placard, according to Denyssen's investigation, was as revenge against Somerset. According to the, slightly conflicting, testimony of several servants George Greig had printed the placard for Edwards and had it posted in a public area where it would be seen. Both denied involvement but they were exactly the culprits the Cape Colony government needed.

The accusations of sodomy against Somerset and Barry were officially ruled as false, untruths concocted by anti-government fringe actors. Anyone involved with Edwards and Greig was arrested and the governing of the Cape Colony continued as normal.

Instead of politically or socially drawing away from Barry Somerset continued to openly support him. There friendship continued seemingly unhindered.

Gossip in Cape Town also continued though.

The entire incident was coyly referred to as having involved Somerset and Barry's wife, or sometimes just as a scandal involving Barry's wife. This was a social shorthand more palatable than actually coming out and saying 'buggery' but meaning the same thing. Mentioning "Barry's wife", carried special significance because as Bishop Burnett wrote "[Barry] is, ever has been, and if rumuor speaks truth, ever will keep single."

It is hard to know if rumors that Barry was a man who preferred men had been widespread throughout Cape Town society before the scandal but they certainly were afterward.

For all that Somerset was better protected in the eyes of society, both by his rank and by his marriage his reputation did not go unscathed either. Samuel Hudson wrote in his diary shortly after the scandal broke that he felt sorry for Lady Mary Somerset to have infidelity and infamy added to Somerset's age and haughty personality.

Somerset and Barry's personal feelings about the scandal have not been recorded. The recounting of Barry bursting into tears is the closest record we have of the way these months worth of investigation and gossip affected them. Denyssen opened his report on the placard and its accused authors by noting that the accusation had no doubt been intended to "wound [Somerset's] heart."

Ultimately, there would be no sodomy trial probably since there was no eye witness of the act to go along with the accusation. The placard and the investigation though was one of a series of events that took place during 1824 and 1825 that effectively ended Barry's career in the Cape Colony and caused Somerset to finally leave his position as Governor.

After 1824 Barry would never again face accusations of sexual impropriety but then Somerset was, as far as we know, Barry's most intimate and intense relationship.

The Barry and Somerset scandal come at the intersection of a number of different issues. The issue of freedom of the press in the Cape Colony and the wider British Empire was certainly a prominent one. Fear of revolution along with growing social and labor unrest throughout Britain saw serious curtailing of freedom of the press along with other civil liberties during the 1820s. The Six Acts passed in direct response to the Peterloo Massacre in 1819 specifically targeted newspapers and other printed material by significantly strengthening the already existing laws against blasphemous and seditious libel. The Six Acts also included The Newspaper and Stamp Duties Act which placed a much higher tax on printed materials including newspapers.

In the colonies, fear of revolution was coupled with fear of slave revolt for those British colonies that still allowed slave labor including the Cape Colony. To retain control over the population of the Cape the British colonial government not allowed independent newspapers that operate in Cape Town. As the non-native population of Cape Town and the Cape Colony, in general, began to grow through control over the presses became harder to maintain.

The 1820s saw a wave of immigrants from Britain and Europe coming to settle in the Cape Colony and this included Thomas Pringle and John Fairbairn. Thomas Pringle was a writer and a poet originally born in Scotland who immigrated to South Africa 1820. He was radical abolitionist and opposed the British Colonial government for continuing slavery within the Cape Colony. John Fairbairn was also originally Scottish and had worked as a school teacher before immigrating to Cape Town in 1823. Fairbrain was strongly reform-minded stemming from his strict middle-class Protestant beliefs. He came to the Cape Colony with the hope of starting a school but struggled to do so within the confines of colonial bureaucracy. When Pringle and Fairbrain began writing the Cape Colony's first independent newspaper, the South African Commercial Advertiser in January of 1824, they did so with the express purpose of using it further social and political reform within the Cape.

Despite the Cape Colony having no actual laws against independent newspapers Somerset and the Cape government still demanded the right to inspect and censor any material before it was printed, which Greig did comply with. The paper also ran at least one article criticizing the Cape Colony government in every issue of the South African Commercial Advertiser published between January and May and most issues included an article calling for greater freedom of the press. There were also articles on why the government should not regulate education in the Cape, one article calling for the abolition of slavery and suggesting that the government was taking money from slave owners to continue the practice. There was an article criticizing the government for too heavily taxing imports and another calling for a mixed government to better represent the different communities living within the Cape Colony. Finally, the South African Commercial Advertiser's article detailing the Edwards' trial all but accused His Majesty's Fiscal of fabricating evidence against Edwards.

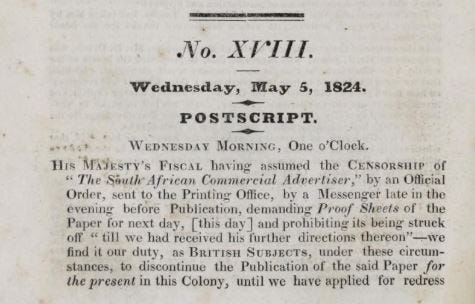

(The first page of the last issue of the South African Commercial Advertiser in 1824)

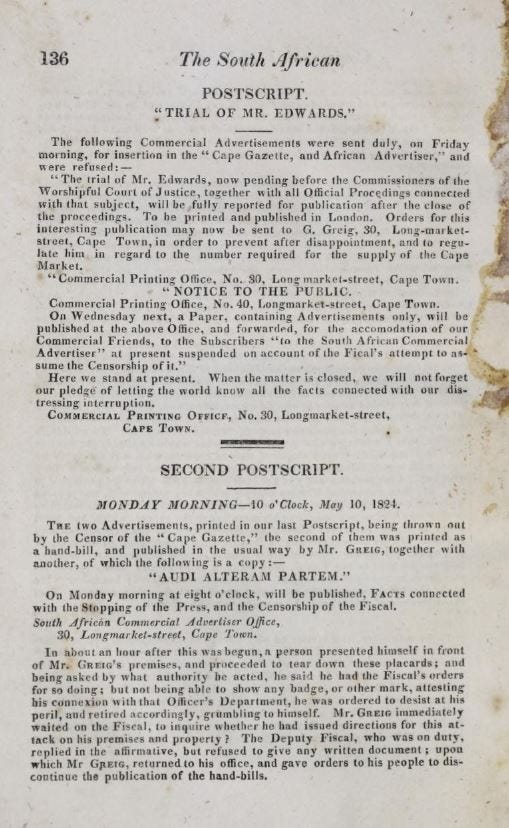

On May 5th Denyssen demanded further rights to censor the paper probably in an effort to stop the flow of articles critical of the government and Denyssen himself. Greig preempted this new round of censorship by shutting down the newspaper but not before sending out one final issue what included all of the correspondence between the newspaper's staff and various government officials along with all of the passages that had been previously censored from earlier issues of the newspaper. On May 10th Somerset empowered Denyssen to make sure the paper remained shut down and to limit private publishers' ability to publish and print independent newspapers.

(A page of postscripts of the South African Commercial Advertiser including passages from older articles that had previously been censored by the government)

Only a few weeks later, on June 1st, the placard regarding Somerset and Barry was posted.

It is important to note that neither Pringle nor Fairbairn were directly implicated in posting the placard. Instead George Greig was accused and arrested for printing the placard. Greig both technically owned, published and printed the South African Commercial Advertiser. By implicating him in printing libel against the Governor the government also guaranteed that the Advertiser could not be quickly restarted. Even if Pringle and Fairbairn were willing to write against the ban Somerset had put on the paper with Greig in prison, is printing pressed almost certainly either confiscated or destroyed, they would have no one to print it for them.

It is impossible to know if Greig and Edwards were actually behind the placard almost two hundred years after the fact. It is important to note though that the accusation of buggery against Somerset and Barry did not happen in a vacuum. In 1824 Britain was seeing a huge influx of sodomy trials and scandals many involving upper-class men. Therefore Barry and Somerset's scandal cannot be seen as an isolated event but in fact as part of a larger story of sex between men during this period.

As Charles Upchurch lays out in his book Before Wilde: sex between men in Britain's Age of Reform throughout the 1820s the number of sodomy cases tried in the courts and reported on by the presses drastically increased. In 1815 Upchurch found fifteen court cases involving sex between in England none reported on by The Weekly Dispatch or the Times two widely read newspapers at the time. In 1825 though there were forty-two cases of which we still have records for with thirty-four articles on the subject of sex between men being printed in the Times and twenty-four in the Weekly Dispatch. This increase did not indicate that more men were having sexual contact with each other but the way sex between men was thought of and policed had begun to shift.

These facts stand in contrast to an older view of sex between men, and sexuality in general, during the 19th century. For a long time, it had been scholars had hypothesized that changing moral and societal views during the later half of the 18th century had led to the erasure of any mention of same-sex attraction particularly between men. From court records to military records to newspaper reports and literature 19th-century British society had viewed sex between men too taboo a subject to even mention. This silence lasted until the late Victorian era where anxieties about a supposed moral decline among the middle class had combined with a growing interest within the medical community to define sexuality medically to create the modern concept of homosexuality.

Upchurch's research and the research of other scholars over the last decade have come to question this narrative of same-sex sexuality and sex between men in Britain during the 19th century. In fact, their work has pointed to an increase not only in sodomy trials during the early 19th century but also the cultural conversations around sex between men.

Seth LeJacq in his article “Rears and Vices: The Austens and Naval Sodomy” addressed a joke in Jane Austen's Mansfield Park that has long plagued Austen scholars. In Chapter 6, when Mary Crawford says: “Certainly, my home at my uncle’s brought me acquainted with a circle of admirals. Of Rears and Vices, I saw enough. Now do not be suspecting me of a pun, I entreat.” Many Austen scholars have maintained that this passage could not be read as a joke about buggery in the British navy because Austen, being well-bred, middle-class lady would not have known enough about anal sex, much less sex between men, to make a joke about it, and neither would her equally respectable readership. As LeJacq and Upchurch point out though this is actually not necessarily the case. In Austen's case both of her brothers served on naval tribunals for no less than ten different sodomy cases all of which were highly publicized. In fact the newspapers were so eager to cover navel sodomy cases that Charles Austen lamented "officers in the Navy are too frequently accused of acts tending to the commission of unnatural offenses… [H]ow frequent are the reports we are doomed at the present day, with grief, to peruse in the public prints.”

Civil cases involving sex between men were just as likely to be reported on as well as Upchurch's research makes clear. Even in court documents many witnesses to men either having sex or soliciting sex from other men reported that they understood and could identify such acts and behavior due to reading them in the paper.

Cases of sex between men involving upper class, powerful or aristocratic men in particular grabbed the public's attention. In 1822 the Percy Jocelyn, Bishop of Clogher, and member of the House of Lords was witnessed having sex with a soldier in a tavern and subsequently arrested. Jocelyn's case, in particular, galvanized the presses because in 1811 Percy Jocelyn had been accused of sexual assaulting a coachman named James Byrne. Not only had Jocelyn leaned upon his power and political influence to have the charges quashed but he'd also accused Byrne of libel for bringing the charges at all. A public spectacle of a trial had followed where Jocelyn had been defended by a number of well known politicians and members of the nobility. All had vouched for Jocelyn's good character as a gentleman and cast doubts on common born James Byrne's character. Byrne ultimately forced to sign a confession alleging the allegations had been a lie and was sentenced to time in prison and public flogging, a punishment he barely survived.

Percy Jocelyn's 1822 arrest, and with it the public realization that Byrne had been telling the truth about his assault, instantly made the case a symbol of class unrest. In the radical and even the liberal leaning presses Jocelyn represented the corruption and hypocrisy of both the Church and the State. What better way to characterize the aristocracy's cruelty and predatory intent towards the working class than a lord who had not only gotten away with sexually assaulting a working class man but managed to get the man beaten within an inch of his life for daring to speak up at all?

(A political cartoon by George Cruikshank depicting Jocelyn's arrest 1822)

Far from thinking of sodomy as too taboo a subject to even write about the luridness of the accusations highlighting the deprived levels that the upper classes had sunk to and the lengths the justice system, the political system and even the church would go to in order to protect them. The situation was made worse when Jocelyn was allowed to post bail and immediately fled the country leaving the soldier, John Moverley, to stand trial by himself.

The link sodomy to state and class corruption being made in even liberal and moderate newspapers was strengthened further when only a month after Jocelyn's arrest Robert Stewart Viscount Castlereagh, the current Foreign Secretary and one of the strongest political voice behind passing the Six Acts died by suicide after confessing that he was being blackmailed for having sex with other men. Between 1822 and 1825 two notable sodomy trials involving members of the aristocracy, John Grossett Muirhead Esq. and Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Archdall both arrested for soliciting sex from working class men, would take place and were covered heavily by the press. While three other members of Parliament either fled the country or died by suicide before accusations could be made.

These cases not only kept sodomy in the newspaper and cultural interest in sex between men running high over the next few years. It also forced a close connection, particularly within radical and liberal newspapers between government corruption and aristocratic men who committed sodomy.

Both the parties who originally created and posted the placard along with the general public of Cape Town would have surely known as well about this connection. The accusation made it plain that Somerset wasn't just a tyrant with his foot on the throat of the common farmers, enslaved peoples and growing middle class of the Cape Colony he was the worst kind of tyrant who committed unnatural acts and used his power to protect both himself and his lover. Not only did this damaging and coded message come hot on the heels of Somerset's banning of the Advertiser but also among growing questions back in England regarding the running of the Cape Colony government under Somerset that would only continue to grow for the rest of Somerset's time in office. When he left the Cape in 1826 it would be to face a Parliamentary investigation into his conduct as Governor although the investigation would ultimately find him not guilty of any major mismanagement.

On top of this, as Kirsten McKenzie points out in her book Scandal in the Colonies: Sydney and Cape Town, 1820-1850 sexual scandal and gossip were more common within the British colonies where they helped to maintain social hierarchy and order. The accusations put forth by the placard were spread throughout the Cape Town's high society Barry's bachelor status became the focus. Barry was both more socially vulnerable than Somerset and also tended not to conform to societal expectations. The gossip around Barry's lack of wife and the rumor that he would never have a wife because he wasn't that kind of a man was meant to reinforce the middle class standards Barry should have been conforming to, but didn't largely through his unusually close relationship with Somerset. Gossip about Barry's non socially normative conduct would only grow as he embarked on his feud with Plasket over the next year. Largely what would loose Barry his job just a year after the scandal was his inability or unwillingness to conform to colonial society's expectations of how someone of his rank and class should have behaved. Barry was by definition an unruly subject and the rumors that he was also queer did nothing to reign that in.

Although the Somerset and Barry sodomy scandal has been given little attention by Barry's biographers it stands at an interesting intersection of social tensions around governmental oversight, social reform and the disruptive power of non-normative sex both at home in Britain and abroad.

Sources Used:

Records of the Cape Colony 1823-1825 https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001260161

James Barry: A Woman Ahead of Her Time by Michael du Preez and Jeremy Dronfield (2016)

Scanty Particulars: The Scandalous Life and Astonishing Secret of Queen Victoria's Most Eminent Military Doctor by Rachel Holmes (2002)

The Revolution in Popular Literature : print, politics, and the people, 1790-1860 by Ian Haywood (2004)

Scandal in the Colonies: Sydney and Cape Town, 1820-1850 by Kirsten McKenzie (2004)

"Politics and Reporting on Sex Between Men in the 1820s" by Charles Upchurch from British Queer History: New approaches and perspectives edited by Brian Lewis (2013)

Before Wilde: sex between men in Britain's Age of Reform by Charles Upchurch (2009)

“Rears and Vices: The Austens and Naval Sodomy” by Seth Stein LeJacq NOTCHES (2018) http://notchesblog.com/2018/12/13/rears-and-vices-the-austens-and-naval-sodomy/

LGBT History Festival Keynote Speech Charles Upchurch (2015) https://youtu.be/_6UYq8o9j2g

LGBTQ histories at the British Library https://www.bl.uk/lgbtq-histories

The Bishop of Clogher; caricature by Cruikshank https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Percy_Jocelyn#/media/File:Percy_Jocelyn_Bishop_of_Clogher_by_Cruikshank.jpg

The First Eighteen Numbers of the South African Commercial Advertiser (collected and bound in 1826) https://archive.org/stream/condensededition00sout?ref=ol#page/n1/mode/2up

A Reply to the Report of the Commissioners of Inquiry at the Cape of Good Hope by Bishop Burnett (1826) https://books.google.com/books?id=BURcAAAAcAAJ&pg=PR10&dq=A+Reply+to+the+Report+of+the+COmmissioners+of+Inquiry+at+the+Cape+of+Good+Hope+by+Bishop+Burnett&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjyoIK776fiAhVDDq0KHTDYDGoQ6AEIKjAA#v=onepage&q&f=false